Dual Loyalties with Britain and Ireland

Irish artist William Orpen spent the majority of his life in England, where he established an extraordinarily successful career as one of London’s most fashionable society painters. In the years preceding World War One, Orpen maintained close connections with Ireland, working part-time from 1902 to 1915 as a teacher at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art (DMSA – now the National College of Art and Design) where he influenced a generation of Irish artists including Beatrice Elvery, Grace Gifford, Seán Keating and Leo Whelan. Many of his letters home to his family in England are written on DMSA headed-paper, and suggest a dual sympathy with Ireland and Britain, during a period of great political and social unrest as Ireland progressed towards independence. Orpen’s letters usually featured witty, self-deprecating sketches, in which the artist would invariably insert himself in the centre of the action.

‘Saw the king yesterday evening – not much of him through the dust – thank goodness they leave today – so Dublin will be at its usual peace once more.’

Illustrated letter from Orpen to his wife Grace, [1911]

Orpen and the British Monarchy

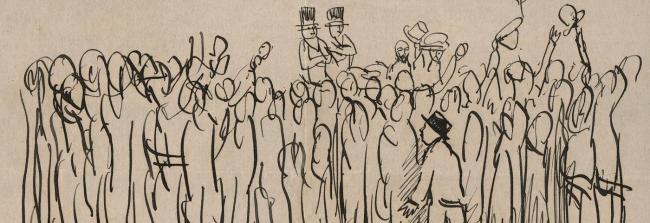

Orpen’s illustrated letters suggest that he attended both the 1907 and 1911 Royal Visits to Dublin. In 1907 he produced a witty likeness of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra being driven in an open-top carriage through central Dublin. The curved classical edifice in the background is likely to be Parliament House on College Green, which the monarchs would have passed on route to Dublin Castle. The streets of Dublin appear deserted, apart from the lone figure of the artist stepping away from the carriage.

Four years later, Orpen sketched large crowds and fanfare for King George V and Queen Mary's visit to Dublin in 1911. Once again he includes a self-portrait: this time Orpen stands on tiptoe, straining to see over the crowds gathered to welcome the monarchs. He writes sarcastically:

‘This is how I saw the King yesterday, it was a grand position.’

In 1918, after gifting his war pictures to the British Nation, Orpen was knighted for his wartime services. However, an undated sketch of him being knighted appears to predate the actual event by several years, as the portly figure of the king resembles Edward VII, who passed away in 1910. This suggests that Orpen aspired to knighthood for many years before it was eventually granted by George V.

‘I have never been able to understand why, if Ulster was allowed to arm, the South couldn’t do the same. However, that’s the way it was.’

Orpen in 'Stories of Old Ireland and Myself', 1924

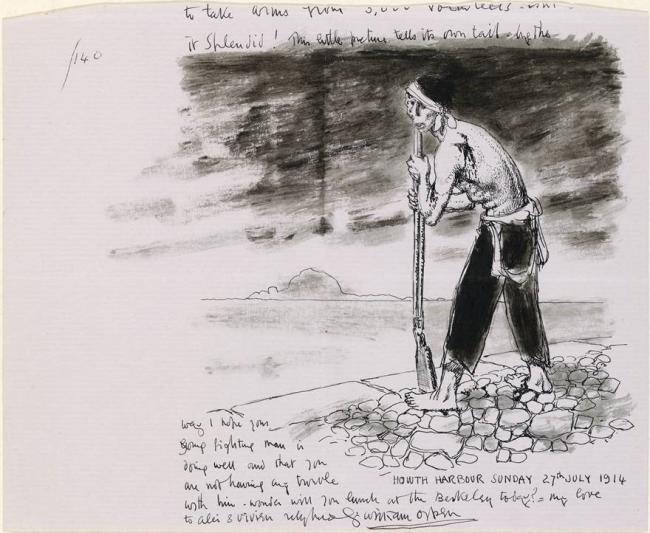

Orpen and the Howth Gun-Running

Orpen witnessed the Howth gun-running first-hand in July 1914, while holidaying in Dublin with his family. The Howth landing was the first military operation in Ireland’s twentieth-century fight for independence, and was a significant development in the lead up to the 1916 Easter Rising. In 1913, Ulster unionists formed the Ulster Volunteer Force, a militia to oppose the increasingly likely prospect of Home Rule in Ireland. The Howth gun-running was a direct response to the Ulster Volunteer Force importing 25,000 rifles into the country in previous months. On 27 July 1914, the Irish Volunteers landed approximately 1,500 German rifles in Howth. In his memoir Stories of Old Ireland and Myself, Orpen describes the great excitement as the little boat came into Howth harbour, and the ease with which the Volunteers evaded British efforts to seize their rifles. Orpen also describes the Bachelor’s Walk Massacre later that day, when British soldiers fired on unarmed civilians in the city centre, leaving 4 dead and over 30 injured.

It was very sad, and made much bad feeling against the British in Dublin at that time.

Orpen describing the Bachelor's Walk Massacre in 'Stories of Old Ireland and Myself, 1924

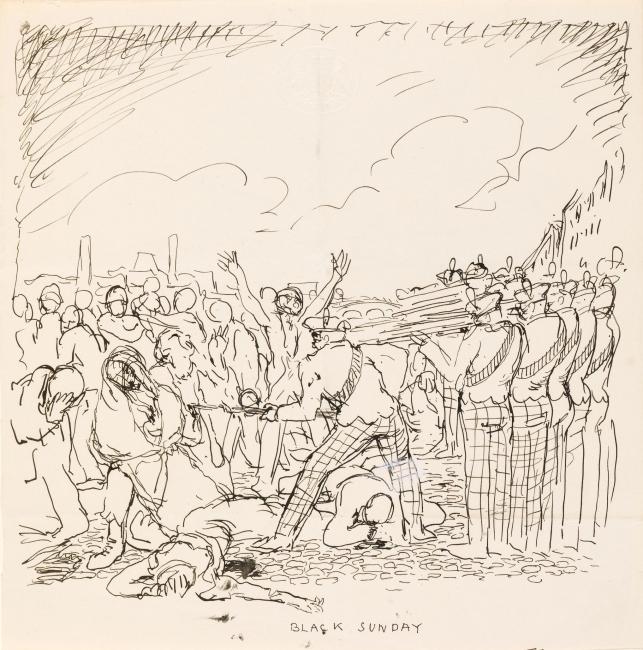

Black Sunday

Orpen’s illustrated letters to his patron and lover, Mrs St George, suggest that his sympathies often lay with the Irish at this time. One striking sketch features a Volunteer who resembles Orpen clutching a rifle in Howth, possibly indicating that the artist identified with their efforts on that July day in Dublin. Another sketch, entitled ‘Black Sunday’, dramatizes the tragic events of the Bachelor’s Walk Massacre. In a composition that recalls Goya’s iconic painting The Third of May 1808 – commemorating Spanish resistance to the occupying Napoleon army – Orpen depicts British soldiers firing point-blank into the crowd and bayoneting women, as nearby victims cover their face or throw their hands up in horror. The soldiers wear tartan trousers and bonnets, identifying them as the King’s Own Scottish Borderers; Orpen would later draw men of the same regiment as a war artist in France.

Ireland! Romance, laughter, and tears!

Orpen in 'Stories of Old Ireland and Myself', 1924

Orpen and Old Ireland

Orpen published his sentimental memoir of Ireland in 1924, three years after publishing his popular WWI memoir, An Onlooker in France, 1917-1919. Stories of Old Ireland and Myself features amusing anecdotes alongside eye-witness accounts of major political developments in pre-War Ireland, including the 1913 Dublin Lockout and Howth gun-running. However, despite his obvious affection for his home country, Orpen returned to Ireland for just a single day between 1915 and the end of his life in 1931. Notably, in a 1929 letter to Lady Gregory (private collection), Orpen writes:

‘When I am allowed to come to Ireland without danger – I most certainly will but at present – and for years past – it seems to me just taking a risk – of asking for it.’

His memoir of Ireland was possibly an attempt to win favour with the New Ireland, and to mitigate his close associations with the British military establishment – particularly his friendship with Major A.N. Lee, who played a significant role in suppressing the Easter Rising and in arranging the executions of the 1916 revolutionary leaders.

A new era has come to the land...No longer are men and women hanged “for the wearing of the green.” Now the shamrock has its place in the sun, and long may it remain there, green and verdant.

Orpen in 'Stories of Old Ireland and Myself', 1924

William Orpen's illustrated letters and memoirs feature in the Decade of Centenaries exhibition, Roller Skates & Ruins, on view in Room 11 at the National Gallery of Ireland until 10 March 2024.

Further Reading

William Orpen, Stories of Old Ireland & Myself, London: Williams and Norgate, 1924

Robert Upstone (ed.), William Orpen: Politics, Sex & Death, London: Philip Wilson, 2005

Marie Lynch, ESB CSIA Fellow

Published online: 2023