Dublin has a large number of fine residential and public buildings, many of the latter were destroyed during the late civil war here but are being rebuilt.

O’Kelly in a letter to James Herbert, 29 January 1927

A Return to Ireland

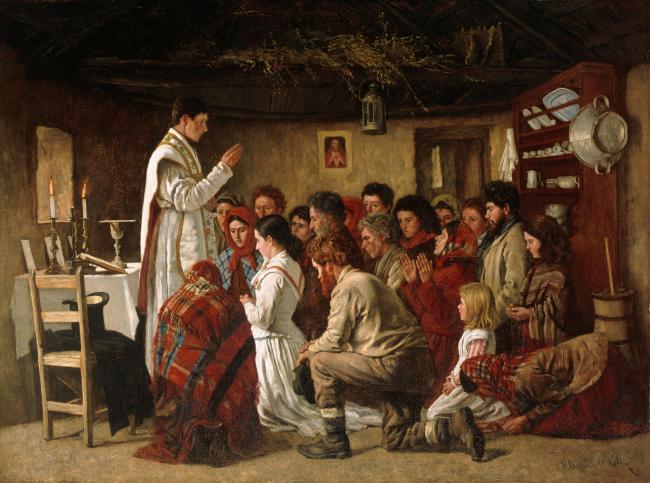

Irish artist Aloysius O’Kelly was an enigmatic figure, who travelled extensively throughout his career. He was among the first Irish artists to attend the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1874, and would establish his reputation in the salons of France with realist genre scenes such as Mass in a Connemara Cabin, exhibited in the 1884 Paris Salon. In the early 1880s, he worked in a journalistic capacity as a ‘Special Artist’ for British publications, covering the anti-colonial campaigns of the Irish Land Wars and the Sudanese nationalist movement. The extent of O’Kelly’s interest or involvement in politics is unclear. He had a close relationship with his brother James, an Irish nationalist politician and member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, and in 1897 the artist put himself forward for election in South Roscommon, without success. However, O’Kelly was absent during the turbulent years of the Irish revolutionary period, living primarily in Brittany and New York. In 1926 he returned to Ireland at 73 years of age, with the intention of creating a new series of paintings of Irish national monuments. His letters to his nephew in New York, James Herbert, provide a first-hand account of life in the newly independent Free State of Ireland. In particular, his descriptions of ruined public, military and residential buildings record the aftermath of the Irish Civil War and the War of Independence.

There are evidences of former trouble in the ruins of the Court Houses and a large police and militia barracks, burnt down during the recent troubles and are now gutted ruins.

O’Kelly in a letter to James Herbert, 12 April 1926

I am glad to have seen the New Ireland.

O’Kelly in a letter to James Herbert, 26 March 1927

Painting the Ancient Monuments of Ireland

O’Kelly lived initially in Tipperary, where he began to paint a new series of picturesque ecclesiastical subjects, views of Holycross Abbey and the Rock of Cashel. Although he was confident that these subjects would appeal to both Protestant and Catholic Deans in Ireland, his letters record that his interview with the Archbishop of Cashel was unsuccessful:

He is a very well-fed looking man with little inclination for art. He appeared to like them but was not moved to purchase. Consequently I came away with the hump.

On 5th July 1926, he wrote a letter to the Registrar of the National Gallery of Ireland, seeking advice for showing his work in Ireland:

In recent years the changes have been so great that I have now no connections in Ireland, and don’t know of any art dealers or of agencies through whom to reach the public…I would be greatly obliged if you will give me some information about what means there are in Ireland for the exhibition of my pictures and bringing them to public notice with a view to sale.

The following year he moved to Dublin and mounted a spring exhibition at the Combridge Gallery on Grafton Street. However, O’Kelly eventually came to the unhappy conclusion that there was 'no buying public' in Dublin at this time and resolved to leave for France, feeling utterly deflated by his efforts.

For the moment I am disgusted with painting and art in general, but will of course inevitably take it up again in France as it is a delightful occupation although disappointing and unprofitable.

O’Kelly in a letter to James Herbert, 26 March 1927

The coal strike in England is punishing us here severely. It is extremely difficult to get fuel at any price and I have considerable difficulty in keeping myself warm.

O’Kelly in a letter to James Herbert, 4 November 1926

The Cost of Living in the Free State

James Herbert managed his uncle's financial affairs from New York, and many of O'Kelly's letters discuss in great detail his expenses and housing arrangements over the course of his year in Ireland. O’Kelly evidently preferred to focus all his efforts on his painting, and he resented any time spent on cooking or cleaning for himself. There are instances of unintentional humour in his descriptions of various landlords and living arrangements:

'He has the British soldier’s weakness for beer and the daughter is much fonder of going to dances and the cinema than working…it means a loss of time doing my own work and cooking.'

However, his letters also offer a remarkable insight into the challenging economic conditions in the young country, which were not favourable to an artist seeking new patrons, as O’Kelly discovered to his dismay. With the approach of winter in 1926, O’Kelly revealed to Herbert his anxieties about costly housing and rising fuel prices, the latter badly affected by a coal strike in London. Nearly a hundred years later, many of O’Kelly’s statements find surprising resonance in contemporary Ireland:

'With a home and money I think life could be very agreeable here, but situated as I am the prospect is not inviting.'

I can imagine that life would be very agreeable in this country for those who are well housed and have plenty of money.

O’Kelly in a letter to James Herbert, 24 November 1926

Aloysius O’Kelly’s letters are held in the ESB Centre for the Study of Irish Art, and feature in the Decade of Centenaries exhibition, Roller Skates & Ruins, on view in Room 11 at the National Gallery of Ireland until 10 March 2024.

Marie Lynch, ESB CSIA Fellow

Published online: 2023