Margaret Stokes

Margaret Stokes (1832-1900), also known as Margaret McNair Stokes, was an artist, archaeologist and antiquary born in March 1832 at York Street, Dublin. She was the daughter of Dr William Stokes (1804-1878), a professor and physician, and Mary Stokes (née Black), originally from Scotland.

Throughout her childhood, Stokes's parents were active in Dublin's artistic and antiquarian scene welcoming guests such as Sir George Petrie (1790-1866) and Sir Samuel Ferguson (1810-1886) to their home on Merrion Square. Stokes later travelled the West of Ireland alongside her father and his antiquarian friends, including the artist Frederick William Burton (1816–1900), researching, photographing, and creating illustrations of historical landmarks.

Stokes began her career by publishing illustrations and illuminations for an 1861 edition of Ferguson's poem The Cromlech at Howth, taking inspiration from the Book of Kells. She contributed to the publications of several other prominent antiquaries of the time and later went on to publish several influential illustrated books under her own name, including Early Christian Architecture in Ireland (1878), Early Christian Art in Ireland (1887), and works about the lives of early medieval Irish saints in Italy and France. Her research interests included historical artefacts such as the Tara brooch, ancient funeral customs, and Irish high crosses, and Stokes frequently presented her research at lectures in Ireland and Britain. Later in life, she began an illustrated text called High Crosses of Ireland; however, she passed away in her Howth home in 1900, before completing the text.

Stokes was a hugely influential figure in the history of Irish antiquities and was one of the most prominent antiquarians and illustrators of her time. She was the first Irish woman to be elected a member of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland and an honorary member of the Royal Irish Academy (she was unable to become a full member as women were not eligible until over 100 years later). Her legacy has ensured that her work has left a lasting impact on our understanding of ancient Irish artistic and architectural heritage.

Irish Antiquities

There was a revival of interest in ancient Irish antiquities and history from the 1840s onwards, partially due to the Irish Ordnance Survey which was completed from 1825–46. Sir George Petrie had been involved in the Survey, heading the Topographical Department. Petrie's work informed his research into early Christian art and architecture in Ireland cumulated in the publication of his The Ecclesiastical Architecture of Ireland: An Essay on the Origins and Uses of the Round Towers of Ireland in 1845.

As well as being damaged by poor weather and vandalism, Irish architectural and artistic heritage had been negatively impacted by the Famine of the 1840s. As much of the Irish population moved away from their native systems of belief, they became less cautious of damaging field monuments such as cairns and stone circles through farm work and land cultivation. Petrie and other prominent antiquaries identified a need for conservation, research, and preservation of this physical heritage.

As well as physical heritage, there was also a revived interest in the Irish language. Margaret's brother Whitley Stokes (1830-1909) became a leading Celtic scholar, studying Old and Middle Irish and Irish literature. Margaret came from a large family, with many relations known for their contribution to the arts and sciences. Little, however, is known about her female relatives.

The Letter

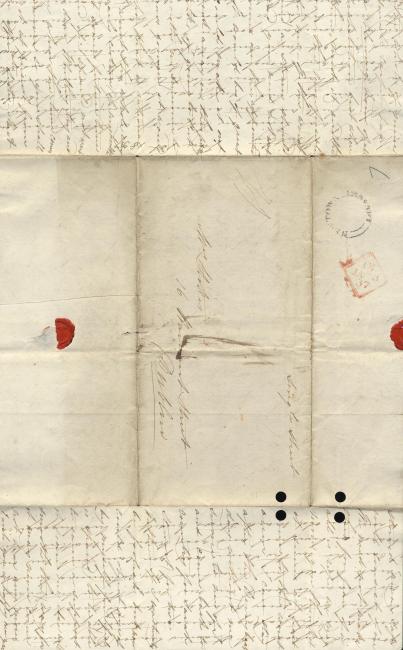

The letter is actually two letters in one. The horizontal letter was penned by Margaret Stokes and addressed to her Brother Whitley Stokes. The horizontal by Sarah Martin (née Stokes) to Ellen Stokes, both Margaret Stokes' aunts and is dated as of the 18th of January 1837, when Margaret was just five years old. It is written using the cross-writing technique, also known as cross-hatching, whereby text is written both horizontally and vertically on a single page. The reader would begin the letter as usual, and once they had read to the bottom of the page, they would flip the paper sideways and continue to read.

This technique was popular in the early 19th century, particularly amongst women who sought to make efficient use of paper resources and save money on postage charges, which remained expensive until the introduction of flat postal rates in the 1840s. When Sarah Martin sent this letter in the 1830s, postage was costed by the number of sheets and distance travelled. The recipient of the letter was charged rather than its sender.

Another money-saving measure was the folding of letters and using the back to detail the address rather than a separate envelope, which would receive a double charge. This letter's cover contains a handwritten address citing Ms Stokes's Dublin home and includes a broken red seal and postmark.

In the letter, Margaret wishes her brother a happy new year, and having not heard from him in a while, offers to come and visit him in Liverpool, asking him to “smooth the way” for her journey and reassuring him that she will bring only “one sensible carry bag”. The affectionate letter captures the close relationship between a sister and brother, two influential antiquaries and scholars, both of whom would have a lasting impact on our understanding of ancient Irish artistic, linguistic, and architectural heritage.